| Table of Contents Page 1 – Introduction Page 1 – Being Cabin Crew Page 2 – Behind the Galley Curtain Page 2 – What a Great Company Page 2 – Employee Mental Health Page 3 – Working Well, Living Better Page 4 – Ex-Police Officer Bart Being Cabin Crew | The Ugly Truth Part 2 |

Ex-Police Officer Bart

As an onboard manager, I always carried out my duties with pride and in a confident and professional manner. I believed in myself, loved working for what I thought was a great airline, and always tried to represent them to the highest standard.

With only one flight manager on each aircraft, we rarely had the opportunity to see how colleagues of the same rank worked. The only time we’d get to fly with another Flight Manager was if we were rostered a flight out of rank.

How some onboard services were delivered and how hard the Flight Manager worked varied greatly. With our rank being the smallest, the cabin crew generally knew most of us and knew who was pleasant to fly with and who could be more difficult.

From what I was told and from my performance feedback, I believe most cabin crew enjoyed flying with me. I worked hard, took care of the crew and was fun and considerate. With that said, I expected a high standard of service and felt comfortable giving direction or feedback when necessary.

During my thirty years with the airline, I witnessed many significant changes. In the 90s, when we checked in for a flight, most of us knew each other. Now, it’s common to check in and not know anyone. Flying with different people several times a month, every month, means relationships have to be built quickly.

One thing that makes Cabin Crew such a great job is that you can check in for a flight not knowing anyone and come home a few days later feeling like you’ve been away with a group of friends. Of course, not everyone always gets along, but for the most part, cabin crew are a nice bunch of people. The one thing they all have in common is that they love good gossip, and there was never any shortage of it.

Several months after being made redundant, I learned rumours were circulating regarding my flight with Bart. Having spent my entire working life with this company, I wasn’t going to allow a pack of malicious lies from a crooked ex-police officer to tarnish my reputation. There wasn’t a shred of evidence to substantiate Bart having been bullied or him or anyone else being touched inappropriately.

I therefore decided to write a blog so friends and ex-colleagues could hear the real story.

Bart submitted his grievance to his manager on January 26th 2019, four weeks to the day after landing home from our trip to Atlanta. The level of disrespect in the complaint was unparalleled and went far beyond what was reasonable or acceptable. Bear in mind he had been in the company for just eleven months and was still in probation.

Having explained in performance feedback that I wrote on him the correct way to deliver the service in First Class, as it’s written in the Service Procedures Manual, he argued that “my version of service delivery was not correct.” I had worked in this cabin since 1995, first as Senior Cabin Crew for two years, then as Purser for four years, and finally as Flight Manager for nineteen years. Bart had never flown as Cabin Crew previously.

Services on the aircraft are run in accordance with procedures laid down by the company. All cabin crew are well trained to deliver services correctly. Each service is led by the Purser, or in First Class, by the Flight Manager if no Purser is on the crew. Some deviation is permitted, but it’s at the discretion of the onboard manager running the service. The variation is generally minimal because that way, everyone knows what they’re doing.

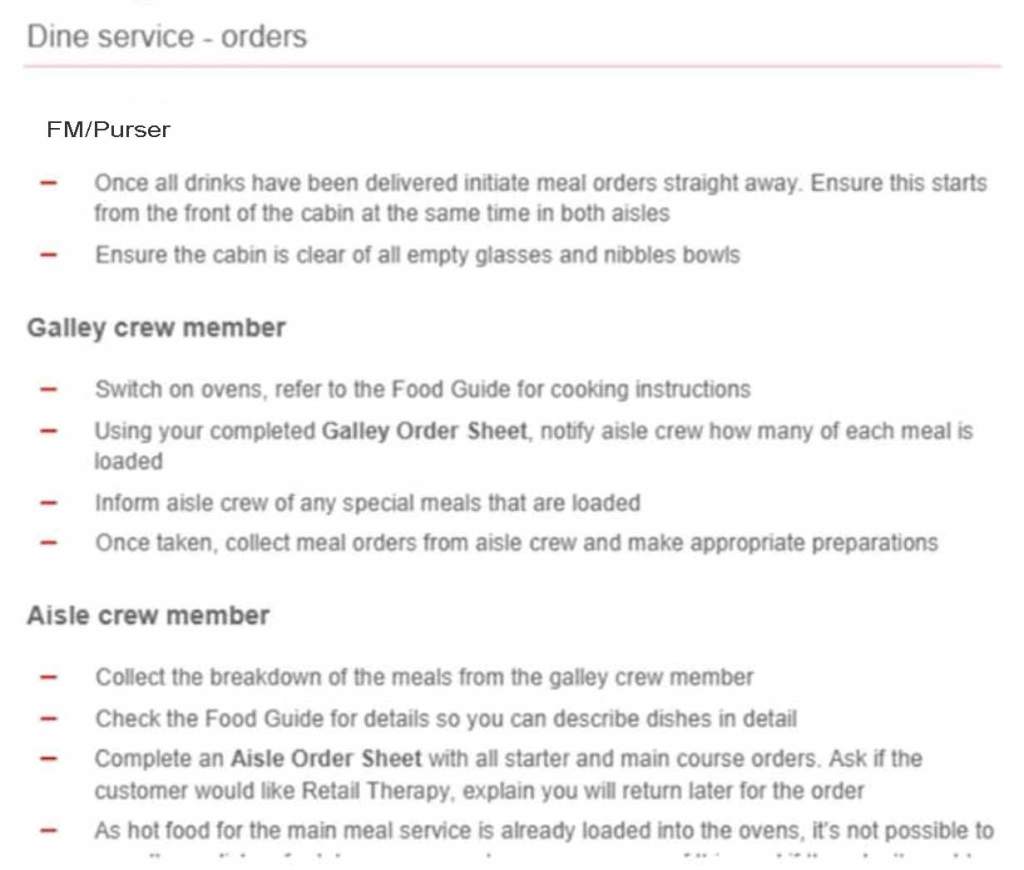

In First Class, after take-off, the crew ask each customer seated in their area what they would like to drink from the bar menu. Once drinks have been served, they return to take each customer’s order for lunch or dinner.

Only a certain number of each hot meal choice is loaded, so depending on what everyone chooses, some people may not be able to have their first choice. To inform a customer immediately if their selection is unavailable, the crew should receive a breakdown of meal choices from the crew member working in the galley. The meals are then distributed equally amongst the two/three crew working in the aisles. Once they’ve used their allocation, they advise the customer that the choice is no longer available.

Upon returning to the galley, any meals that have not been used can then be offered to people who may not have received their first choice.

I liked doing the service this way; however, for reasons I never understood, the crew did not. They preferred to take all meal orders and hoped there would be enough to go around. What often happened was that too many of one choice would be ordered, so they would have to go back to a customer to ask for a second choice.

The number of meals loaded depended on the number of customers in the cabin. With fewer people, fewer meals would be loaded. If you had ten people instead of forty-five, you may only have fourteen meals. This minimised wastage, which saved the company money.

On our flight to Atlanta, we encountered a forty-minute delay before the aircraft pushed back from the stand. The door was still open, and I was waiting to be advised when it could be closed. From where I was standing, I could see Bart on the opposite side of the cabin, going from seat to seat, talking to his customers. I thought it was a nice touch. What he was actually doing was taking after takeoff drink orders and an order for lunch.

When I discovered he had done I was, understandably, not very happy. I told him that’s not how the service is delivered and then explained how it’s done correctly.

It was very rare for drink and meal orders to be taken before take-off. It occasionally happened, even though it shouldn’t, on flights that left very late in the evening with a full First Class cabin. It would never be done on a nine-hour flight leaving before midday with a half-empty cabin.

The following screenshot comes from the performance feedback that I wrote on Bart. I was advising him of the correct way to deliver the service:

The following extract comes from my defence in response to the initial complaint that Bart submitted along with his grievance.

The orange font is my response:

The following also comes from Bart’s complaint:

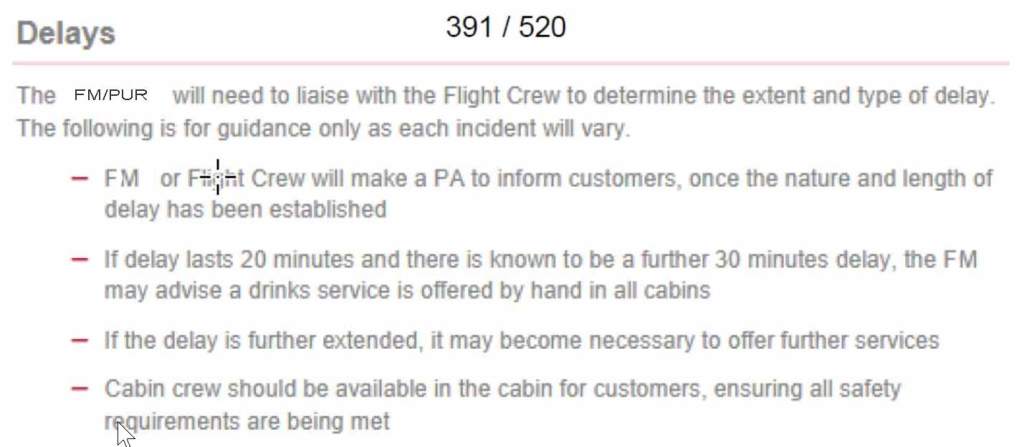

This was a forty-minute delay, so was far from “unusual circumstances.” Bart had been flying for eleven months and told me he had worked in this cabin many times.

Our flight to Atlanta was almost nine hours. Customer Relations confirmed we had twenty customers in First, not nine. Six crew members were working in the cabin. Had there been nine customers, as Bart claimed, each crew member would have had three people to serve. Yet he wanted to “save time in the air”. But as you’ll see, his story continually changes.

If the cabin had been full, which it usually was, the same six crew members would have been looking after forty-five customers.

The manual that dictates how services are delivered can be accessed on each crew member’s company iPad. However, if Bart had any questions, he could have spoken to me, Katrina, Lottie, or Claire.

Bart didn’t inform anyone what he was doing, and it only became apparent after take-off when he was asked to start taking his drink orders.

In this next screenshot, which is from the minutes taken during my first meeting with Cabin Crew Manager Lana, Bart claims that my comment from the performance feedback that I wrote on him is bullying because it’s an inappropriate/derogatory comment about his performance.

Part of the role of a Flight Manager is coaching and developing their crew. I had been writing performance feedback on cabin crew since my promotion to Purser in 1998. I was promoted to Flight Manager in 2001.

Providing constructive feedback to advise how something should be done correctly is neither inappropriate nor derogatory. When I discovered that Bart had taken his orders before take-off, I explained that this was not how the service was delivered and then explained the correct procedure.

You’ll notice Bart states he took his orders because customers started telling him what they wanted to eat/drink after take-off. Yet, in his written complaint, he says he took orders to save time in the air.

So, Bart approaches each passenger seated in his area before the aircraft door has even been closed. Having only been on the aircraft a short time, people are still familiarising themselves with their seat and the environment. Yet instead of engaging in polite conversation, they start telling him what they want to drink and eat after take-off. And it wasn’t just one passenger who allegedly did this, it was every passenger he was looking after.

It’s worth noting that none of the passengers on this flight from Heathrow to Atlanta had flown with the airline before.

The following screenshots are from my defence. The black text is from Bart’s complaint, blue is my response. All crew members’ names have been changed.

As cabin crew, you need to use your initiative, but working as part of a team means working together and communicating with each other. Services are delivered in a specific manner on an aircraft and it rarely changes from one flight to the next. Regardless of the cabin you’re working in, you only begin the service when instructed to do so by the Purser or Flight Manager. All cabin crew are fully aware of that because it’s the same on every single flight. That’s why there’s someone in each cabin who leads and directs the service.

Having explained to Bart how the service should be done, he argued, as you can see in point 10 above, that despite looking through the Service Procedures Manual “in-depth,” he cannot see where it’s written. So despite having worked in the First Class cabin many times, he’s totally unfamiliar with the most basic part of the service.

As you’ll see as my account of this situation progresses, he really had no idea what he was doing and was just making things up as he went along, hoping that nobody would notice. I now believe this was the first time he had ever worked in First Class.

He also states he was not guided on the ground as he has been in past delays. Yet this is someone who took an instant dislike to me because he wasn’t given the opportunity to work up as Purser. We hadn’t even taken off, and it was already apparent that he had no idea what he was doing.

In a delay, there is very little the crew can do except wait, be patient and follow any directions they’re given by an onboard manager.

A crew member on a full-time flying roster flies five to six times a month. One flight includes an outbound sector, at least one local night in the destination and then an inbound flight. With Bart having been with the company for eleven months, he would have done around fifty-five flights or one hundred and ten sectors.

The following two screenshots come from the company’s Service Procedures Manual.

After take-off…

After the Head of Cabin Crew dismissed my appeal, I decided to take the matter to an industrial tribunal. I had more than enough evidence to prove that Bart and several other crew members were lying and that the matter had not been investigated properly.

I submitted a twelve-page grievance against the company for the way the Head of Cabin Crew handled the matter and also wrote individual grievances against crew members Bart, Anna, Mia, Peter, and Ven.

I was advised by ACAS (the government’s Advisory, Conciliation, and Arbitration Service) that this had to be done before I could submit a claim to an Industrial Tribunal.