| Table of Contents Being Cabin Crew | The Ugly Truth Part 1 Page 1 – 2018 – My Return to Work Page 1 – Monitoring Performance Page 2 – My Performance Record Page 2 – Performance Feedback Page 3 – The Early Days… Page 4 – More from the Good Old Days Page 4 – Cabin Crew Life Downroute Page 4 – Pre-Flight Safety Briefings Being Cabin Crew | The Ugly Truth Part 3 |

More from the Good Old Days

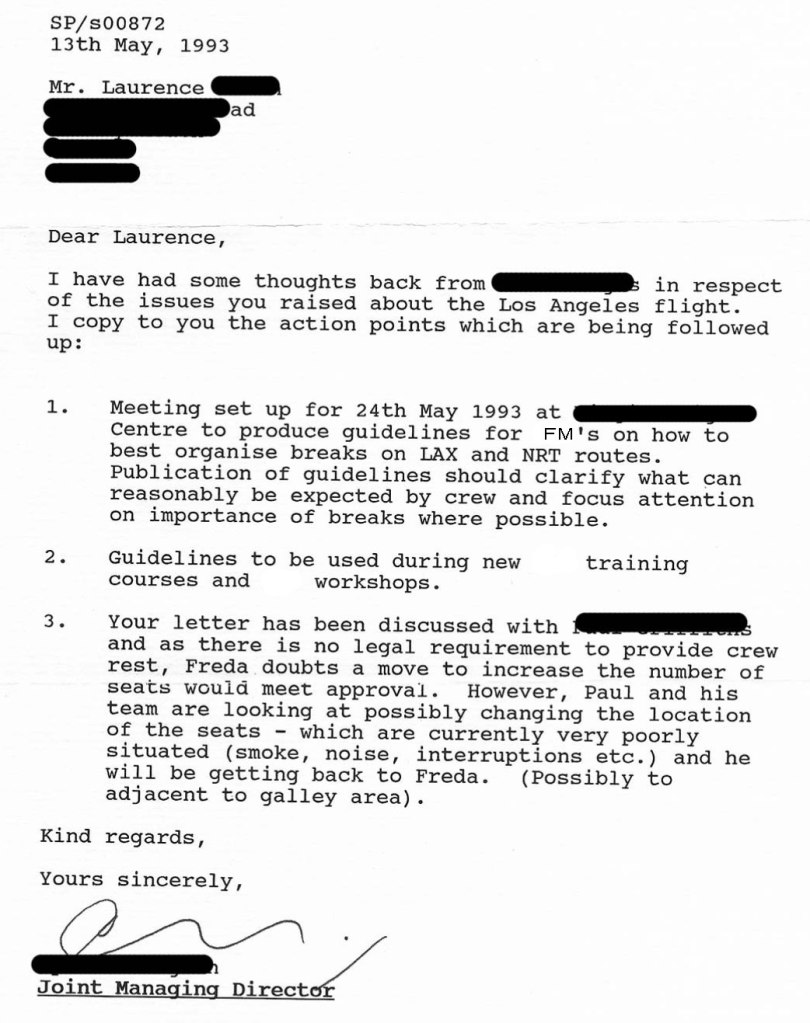

In the 1990s, with just six aircraft and a handful of destinations, the flights were always full. Working in Economy as Junior Cabin Crew was hectic and tiring. We rarely had a rest break because there was nowhere for us to sit. On a day flight, we’d be on our feet from take-off to landing. The East Coast of the USA was manageable, but the West Coast was a killer. The flight to Los Angeles could be close to eleven hours.

On night flights, after the main services had finished, we’d sit on large galley storage boxes reading newspapers and trying to stay awake. Night flights were always difficult, but we didn’t know any different.

In later years, the company would sometimes block off four seats in Economy to share between eighteen crew members. This enabled us to have a short break. The seats were at the back of the aircraft in the smoking section, adjacent to the toilets, and were sometimes screened off by a curtain. If the flight was overbooked, which it often was, the seats would be used for passengers.

Breaks were at the discretion of the Flight Manager, and many weren’t keen on giving them.

The company encouraged us to write in with suggestions, so in 1993, I wrote about the lack of breaks on West Coast U.S. flights and also flights to Tokyo.

Two existing aircraft were fitted with bunks up in the tail towards the late 1990s, and some of the newer aircraft that joined the fleet also had bunks. Despite that, breaks for Junior Cabin Crew were still rare. The Senior Cabin Crew would often be given a break on night flights because their services took far less time to complete.

From about 2004, on West Coast U.S. flights, the company agreed to leave four seats in the last row of Economy free. By the time we started breaks, passengers had usually moved into them, and we were not allowed to move them out.

In recent years, with most aircraft having crew bunks, breaks were given on most flights, time permitting.

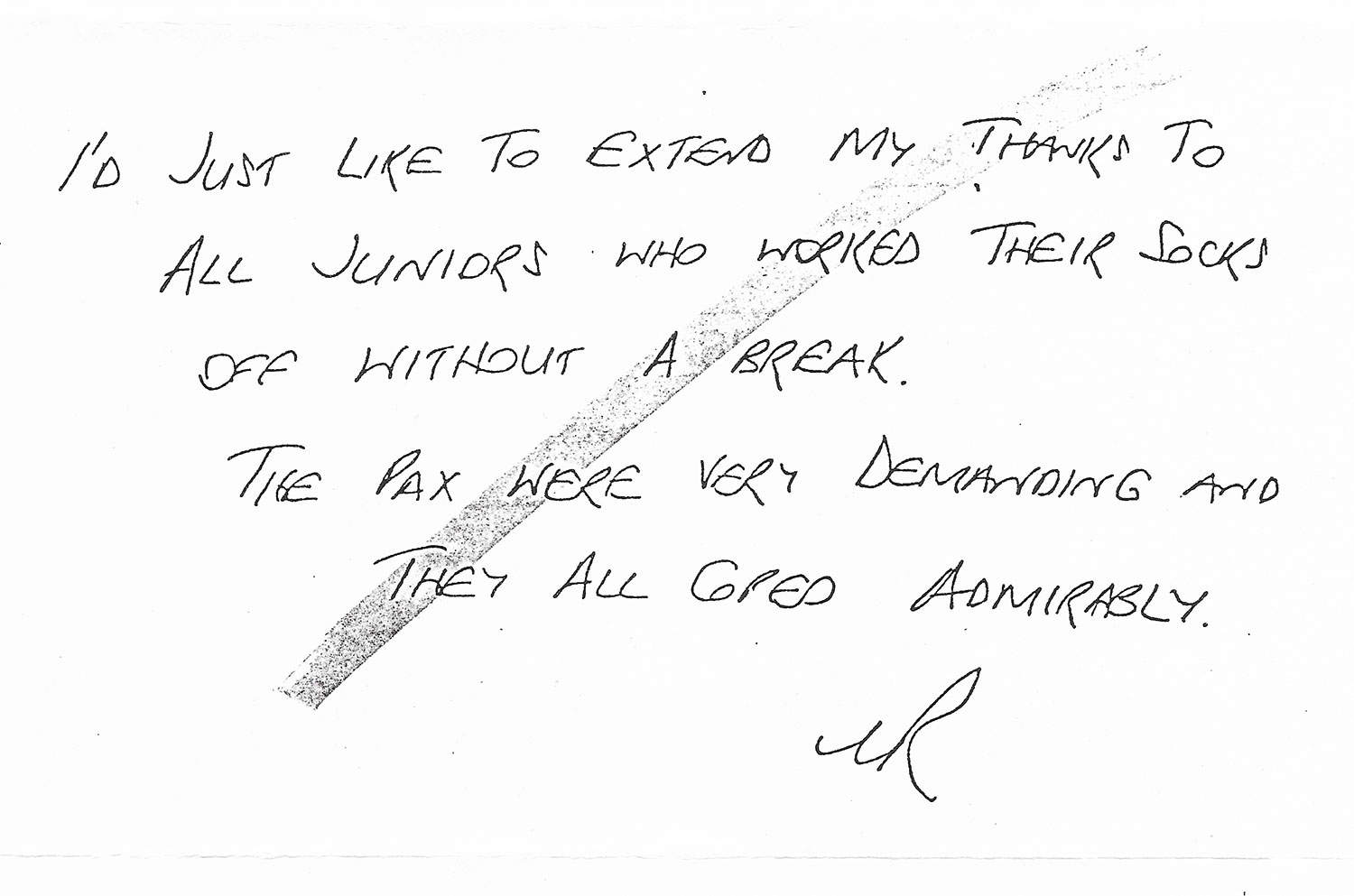

Flying long haul, especially full-time, is extremely tiring. Throughout my time as a Flight Manager, I always tried to give my crew a break on both sectors, provided it didn’t jeopardise the standard of service. I expected them to carry out their duties to the highest standard, led by example, and worked hard alongside them in all three cabins.

I was supportive, approachable, and always ready to laugh and joke, which created a fun and friendly atmosphere.

This photo was taken on a long night flight home from the U.S. sometime between 2002 and 2006. These four seats at the back of the aircraft in front of the toilets were used for ‘crew rest’. They were not curtained off and had to be shared between sixteen crew. Breaks began after the dinner service and ended before the breakfast service began.

The working environment during the 1990s was very regimental, and there was great respect for seniority. Junior Cabin Crew rarely went into First Class, even to use a toilet, and Senior Cabin Crew never went through the curtain to Economy.

The Seniors ate food that hadn’t been used during the First Class service, while the Juniors ate anything left over from the Economy service. A ‘crew food’ cart was loaded, but the selection was usually dire. Portion sizes were tiny, there was never enough to go around, and the menu rarely changed.

On the crew transport bus to the hotel, the Captain and First Officer sat at the front, the Flight Manager sat behind, followed by the Pursers and Seniors, and the juniors always sat at the back.

Upon arrival at the hotel, we collected our room keys in the same rotation. There was no resentment because that was just the way it was. Despite how it may sound, it was a good company to work for, and most of the cabin crew were lovely.

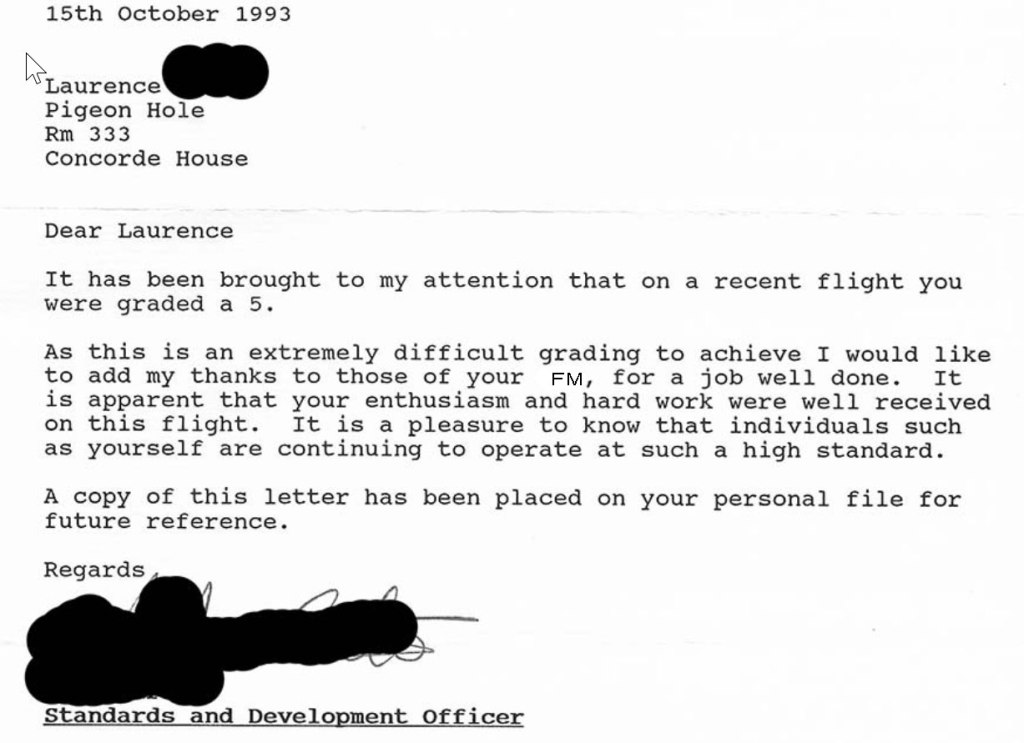

In the early years, it was common to receive a letter from your manager when you did something well. In later years, it was very rare, however, if you did something wrong, you’d hear almost immediately.

I was Junior Cabin Crew for four years, which was unheard of in those days. When the Gulf War broke out in 1991 people stopped flying, so flights were virtually empty. As a result, recruitment and promotion dried up. I was eventually given my Senior Cabin Crew course towards the end of 1994.

After two years of being a Senior I gained promotion to Purser.

From the late 1990s to the mid-2000s, there was a dramatic decline in the level of respect for seniority. While some change was inevitable, it happened too quickly and went too far.

As the airline modernised, Senior Cabin Crew gradually began helping in Economy after services in First Class had finished. Juniors who were brave enough also ventured into First to use the toilets and to ask if there was anything left over from the service to eat.

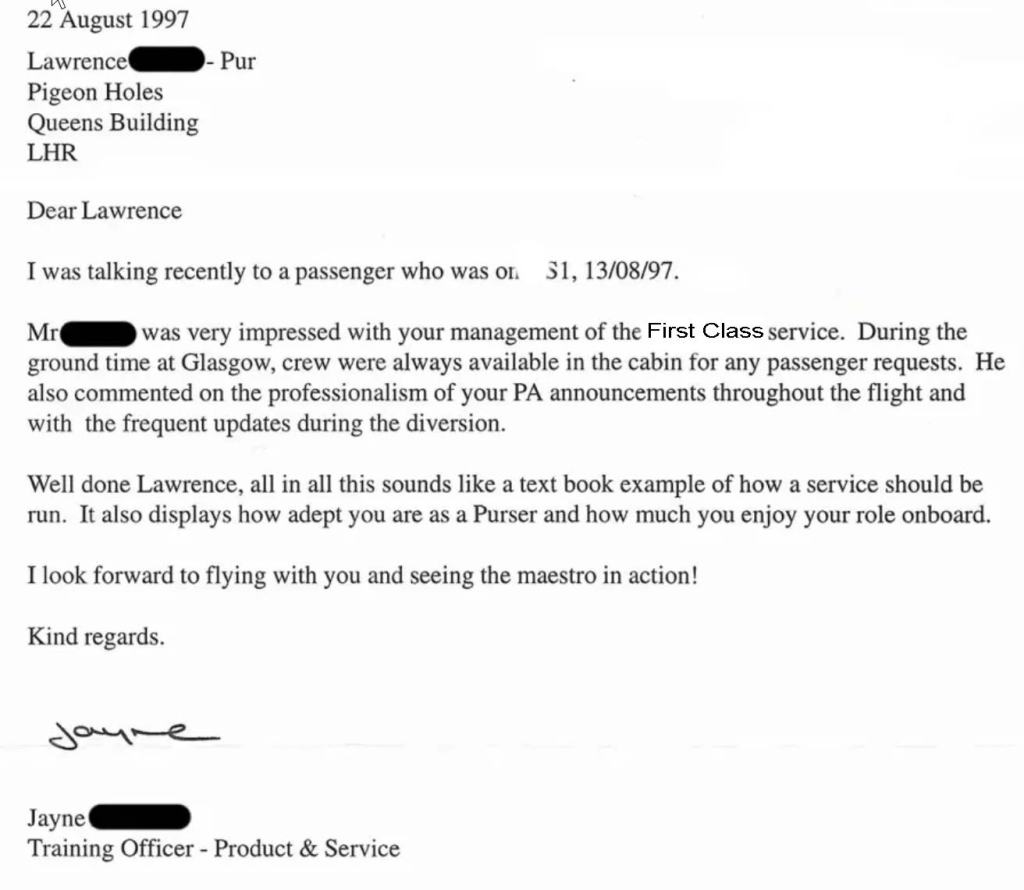

I’ve included the following letter because it’s relevant to comments about my performance and ability made by Bart in his grievance and by Anna and Ven in their witness statements.

You may recall from an earlier chapter that my onboard announcements were also praised in my manager’s performance appraisal.

Cabin Crew Life Downroute

Upon arrival at the hotel, while waiting to collect our room keys, someone would usually organise a ‘room party.’ In those days, each crew member was allowed to take a small amount of alcohol off the aircraft, but it was widely abused. At a room party with eighteen young cabin crew, there was rarely a shortage of something to drink. Fancy cocktails made up in empty water bottles often appeared out of nowhere.

Room parties were common, and most of the crew would attend. They were sociable, rowdy, incredibly smoky, and totally unpredictable. They were always fun, but some were more fun than others.

In the days before the internet and social media, we engaged with each other more spontaneously, and interactions were more genuine and meaningful.

Depending on the length of the layover and destination, the crew would often stick together. We’d usually meet for breakfast and then decide how to spend the rest of the day.

If we had more than one night away, we’d go for dinner as one large group, which usually ended in disaster because too much alcohol was consumed, and there were always arguments when splitting the bill.

The early years were so much fun. It really was the best job in the world.

Some crew members you would fly with quite often, while others you may not see again for many years, if ever. On one of my first flights back in 2018, after being on long-term sick leave, I flew with someone who I hadn’t seen since we were Juniors.

Despite so many years having passed without any contact, within no time at all, we were like two old friends who had never been apart. That kind of connection wasn’t unusual for those of us who had been with the company since its early years.

In August 1990, during a layover in Los Angeles, we went horse-riding up to the Hollywood sign. It sounds really cool, but the horses just followed each other in one long line. It stands out in my mind because, on the way back down, they walked on the very edge of the path and immediately to our left was a sheer drop into a deep canyon.

When we reached the bottom, the ranch staff were gathered around a radio, listening to the news. America had just bombed Baghdad. It was the start of the first Gulf War.

The airline struggled through the next few years, but when things picked up they leased more aircraft and several new routes were introduced.

Having finally been promoted to Senior Cabin Crew, I loved working in First. Unlike Economy, the cabin was calm and spacious, and there was plenty of time to chat with customers.

Being someone who was once very sociable and loved to talk, I could usually be found at the bar playing barman whilst exchanging stories with people from all walks of life.

Life was good, and my work life could not have been happier.

Pre-Flight Safety Briefings

As cabin crew, once you arrive at the Cabin Crew Check-In area for your flight, you wait to be called for the Pre-Flight Briefing. Led by the Flight Manager, it lasts for around twenty minutes. This is the first time the entire crew get together.

The purpose of this meeting is to discuss the flight, services, and safety onboard. Each Purser also delivers a short service-related briefing. It’s an opportunity for the onboard managers to set the tone for the day and to mention anything they want the Cabin Crew to be aware of.

The UK Civil Aviation Authority requires each crew member to be asked at least one safety-related question. This is the most nerve-racking part and once over, everyone begins to relax.

The Flight Manager asks each crew member a question individually. If they’re unable to answer or answer incorrectly, they must be asked a second question. Failure to answer can lead to you being removed from the flight.

In thirty years with the company, I had never witnessed anyone being ‘stood down’ (which means being removed from the flight) because they could not answer their safety question. That said, it certainly happened, albeit rarely.

The safety questions for the Pre-Flight briefing were written by the safety department. They came from the Safety and Emergency Procedures Manual, which all crew must be completely familiar with.

Until 2003, Flight Managers wrote their own questions so the cabin crew could be asked anything from the entire manual. Thinking back to my early years before being a Flight Manager, I remember how nervous I felt while waiting to be asked my question. When it was your turn, all eyes in the room were on you, and there was a deathly silence. As a Flight Manager, I always tried to take the pressure off as much as I could because everyone hated that part of the briefing.

In later years, the safety department issued the questions. The cabin crew were informed which section of the safety and procedures manual they came from so they could familiarise themselves with the chapter. The same questions were used for several months so it wasn’t long before the crew knew the answers.

I want to explain something that will make more sense as you read on, so please bear with me.

The way the company wanted Flight Managers to conduct the pre-flight briefing changed many times over the years. A couple of months before my Christmas trip to Atlanta with Bart, during a conversation with my manager, he told me they wanted briefings to be more interactive. With the Flight Manager conducting the briefing, they do most of the talking, and they wanted the cabin crew to become more vocally involved from the start.

There was already a huge amount to cover, and the briefing could last no longer than twenty minutes. One of the first things we had to do was read out some ‘aircraft familiarisation points’. With us all flying on different types of aircraft several times each month, it was an opportunity to refresh everyone’s memory regarding safety equipment and procedures on the aircraft we were about to fly on.

The safety department wrote seven points, which never changed. The same seven points were included in every Pre-Flight Briefing regardless of aircraft. The Flight Manager was required to read out “at least” three of the seven points. Following the conversation with my manager, I decided that instead of reading the points out, I would ask them as questions to the group as a whole. That would act as an ice-breaker and get everyone involved from the start.

I compiled a list of questions that included the seven points and added an additional two of my own. Those questions were, “How do you make an emergency announcement using the interphone system on this aircraft” and “How do you make a regular announcement.” I thought they’d be beneficial because the interphone system varied from one aircraft type to aircraft. The information is in the Safety and Emergency Procedures manual that all cabin crew are required to know and are tested on thoroughly once a year.

Having a list of nine points meant that I didn’t have to ask the same questions in every Pre-Flight Briefing. Due to time constraints, I’d usually ask about four, depending on the response.

On my flight to Atlanta with Bart, ten crew members with experience ranging from six months to eight years were present in the Pre-Flight Briefing. Ven, who had been called out for the flight from standby was not present.

The following extract comes from the witness statement of Anna, Bart’s now ex-fiancée. The black mark obscures Bart’s real name.

“Positions were assigned” refers to me allocating inflight working positions myself instead of allowing the crew to choose where they wanted to work. During the briefing, I asked safety-related questions twice. The first time was the aircraft familiarisation points that I asked as questions to the group as a whole. Having explained what I was about to do, I said, “Just shout the answers out.”

Each crew member was then asked an individual safety question, which is a mandatory part of the briefing and happens during every Pre-Flight Briefing without fail. The questions are read out from the Flight Manager’s iPad. The briefing questions I asked had been in use for the previous three months, so the crew would have heard them many times before.

Anna claimed that she and Bart were asked more difficult questions than anyone else, yet I was unaware that they knew each other, let alone were engaged to be married. The only crew member I had flown with previously was Bruce.

Nothing that Anna said in her witness statement was supported by anyone else on the crew except for Bart. As you’ll see from her answers, she’s a malicious, vindictive and incredibly hateful individual with the typical traits of a sociopath.

Here’s another extract from her witness statement. The black mark covers my surname. She had been with the company for about eleven months and had been cabin crew previously with another airline.

PAs refer to my onboard announcements.

As part of their witness statement, the crew were asked the following question:

“Please share any observations on Flight Manager Laurence’s PAs onboard the aircraft. Were you aware of any feedback from crew or customers regarding his PAs?”

In his grievance, Bart stated that all of my P.A.s were “long and rambling.” He claims my after-take-off announcement was more than five minutes long, yet Ven states I didn’t make an after-take-off announcement. No other crew member had any recollection of my announcements or was aware of any complaints from passengers or crew members.

Peter, who had been with the company for six months and had never flown as cabin crew previously, brought a friend with him on a staff concessionary ticket. It was her first time flying as a passenger with the airline, and she had never been cabin crew. In his witness statement, he wrote: (quoted verbatim)

“I can’t recall any customers commenting on his PA’s but I took a companion and she did mention his PA’s were really long and didn’t need to be.”

Having spoken to Customer Relations while compiling my defence, I was told no complaints had been received regarding the service on this flight. I could also see from the Voice of the Customer post-flight questionnaires that there were no comments regarding onboard announcements.

This extract is from Ven’s witness statement.

After take-off, while the cabin crew are still in their seats, the Flight Manager makes a mandatory announcement in which they introduce themselves and explain some safety procedures that passengers must comply with.

Tommy, who worked up a rank as Purser in Economy, was unable to confirm anything about my announcements. The following extract is from his witness statement:

If his comment about my announcements not sounding particularly professional is true, it should have been noted in the upward performance feedback that he was required to complete on me. The feedback is anonymous, so it’s not shared with the Flight Manager at the time. Tommy didn’t do feedback on me or the cabin crew he was in charge of, despite it being mandatory for both sectors.

Surely if he had been told my announcements didn’t sound particularly professional, he would have listened to other P.A.s that I made during the flight so he could judge them for himself. After landing, the Flight Manager makes another announcement so that would have been an ideal opportunity.

Considering Bart claimed my P.A.’s were more than five minutes long, only Ven and Anna were able to remember anything about them.

I assume that Ven found my P.A.s “strange” because instead of reading them from the P.A. book, I often ad-libbed them, which not many Flight Managers did. In his four years of flying, it was clearly not something Ven was used to.

As you may recall from an earlier chapter, the style of my onboard announcements was praised in written correspondence and in more than one performance appraisal written by my manager.

Our outbound flight to Atlanta, which was a day flight, had very few passengers. Therefore, I was able to give the cabin crew a two-hour break in the bunks. I didn’t take my break because six of the eleven crew members were relatively new, and two were working up a rank in supervisory roles, so I didn’t feel comfortable leaving the cabin.

In this next extract which comes from Tommy’s witness statement, he is asked about Bart’s engagement with customers. Tommy was working in Economy at the back of the aircraft, and Bart was working at the front. In his response, he talks about my engagement with customers.

His response regarding seeing me in Economy (at the 3 doors jump seat during turbulence) is relevant because of something that Bart, Anna and Ven state in their witness statements.

Our outbound flight was quiet and problem-free. With it being Christmas Eve, the company had asked the hotel in Atlanta to put on a buffet dinner for us that evening, which included an open bar. After dinner, some of the crew went out, but the Captain, First Officer, Lottie, and I returned to our rooms.

The following morning, a few of us met in the restaurant to have Christmas breakfast together. I then returned to my room and slept for a few hours to prepare for the night flight home.

I’d enjoyed the trip but was looking forward to seeing my dad. Before leaving my room to check out, we had spoken, and he sounded really weak. Just before boarding the bus to the airport, someone asked everyone to gather for a photo. Many of the crew grabbed cameras and several photos were taken.

Although I’ve masked faces for anonymity, this was a very happy photo. It had been a nice trip, it was now Christmas Day, and everyone was in high spirits. The eyes are the window to the soul, and by masking them, it’s difficult to appreciate the atmosphere.

In her statement, Mia accused me of touching her leg during the short period that she was helping out in First Class. Yet according to witness statements written by other crew members, nobody was aware of, or saw me touching anyone inappropriately at any time, except for Bart and Anna.

As I’ve already mentioned, Peter and Mia are best friends. Look at the next two screenshots. The first is from Peter’s witness statement, and the second is from Mia’s.

Even though Mia is lying, as I’ll prove later, she says, “I don’t wish for this to be taken further.” If she didn’t want it to be taken further, why mention it? I believe she was being coerced by Anna, who wanted her to support her and Bart’s allegations of inappropriate touching. I’ll provide evidence to support this shortly. Remember that Mia and Anna were already friends prior to this flight.

Here’s another extract from Anna’s witness statement. Before reading it, take another look at the photo above. Anna is on the left in front of Bart, she’s the only crew member who didn’t wear a company-issued Christmas sweatshirt for the flight home. I’m five feet seven.

I find it interesting that if I was behind her with my hands on her hips, how did she know I was “hunched over?”

Something else to consider is that Bart, an ex-police officer of eight years, is a “fairly confident individual”, according to what he wrote in his grievance, yet when a man allegedly touches his fiancée in a way that makes her feel uncomfortable, he fails to address it.

I had no engagement with Anna during our outbound flight to Atlanta. On our return flight to Heathrow the following day, she came to the front of the aircraft just once and stayed for only a few minutes. I rarely had the opportunity to go to the back where she was working because the flight was full and extremely busy.

During my first meeting with Cabin Crew Manager Lana, which took place before witness statements were sent to the crew, I was asked how I would touch someone on the aircraft if I had to move them out of the way. My answer can be seen below. This extract is from the appeal that I submitted to the Head of Cabin Crew.

So, despite my alleged touching making Ven, Anna, and Bart feel “very uncomfortable”, which all three repeated multiple times in their witness statements, they said nothing about it to anyone during the flight, while in Atlanta or after returning home.

The only physical contact that could be confirmed through my own admission was the moment I touched Ven’s ankle while having a joke with him. Not only was the incident witnessed by Katrina and Lottie, but in her witness statement, Lottie says, “Laurence appeared to me to be in very high spirits towards the end of the inbound sector and was laughing and joking with the crew.”

Other than allegations made by Bart, Anna, Ven and Mia, who said she didn’t want my alleged touching of her leg to be taken further, there is not a shred of evidence to support my touching anyone at any time. Other than the lies told by Bart and Anna, nobody saw me touching anyone inappropriately at any time, and nobody was even aware of any such behaviour, except for Peter, but what he said in his statement contradicts what Mia said in her own statement.

Therefore, in carrying out her investigation, the Head of Cabin Crew relied on responses from Anna, Ven, and Mia despite my having provided extensive evidence which proved they were lying

The following extract comes from the Head of Cabin Crew’s investigation:

To further prove what a malicious, nasty and prolific liar Anna is, she stated in her witness statement that she and Mia complained to a Cabin Crew Manager about “my behaviour” when they checked in for their next flight. You would have thought they would have mentioned the inappropriate touching.

While compiling my defence, I spoke to the Cabin Crew Manager to ask about the complaint. She told me nothing was said about inappropriate touching, but had it been mentioned, a full investigation would have been launched immediately.

She explained the only thing that Anna and Mia had complained about was the email they received from me on their days off. That’s quite brazen, considering both of them were still in their probation period.

The email they’re referring to was sent after the flight to thank them for their hard work. I also shared the results of the Voice of the Customer questionnaires from our inbound flight to Heathrow. A flight Manager is not required to do this, and I had never done it before.

I did it on this occasion because a customer in Economy made a negative comment about the way he had been served by one of the female crew members. There were three female crew in Economy, including Anna. Having worked with Mia on the outbound and inbound sectors, I noted she had a very nice manner when serving customers.

With Anna and the other female crew member still being relatively new and Tommy working up in a supervisory role, I thought sharing the feedback would benefit their development and they’d be interested to hear it.

The scores given to the cabin crew affect the performance scores of the Purser and Flight Manager and were also used to decide who would be made redundant.

Being Cabin Crew | The Ugly Truth Part 3